Market size is crucial. Most pitches get wrong.

“Our new product will disrupt a $47.9 billion dollar market growing at a CAGR of 7.3%.”

Listening to early-stage startup pitches, I’m constantly bombarded with bombastic claims like these. When I dig in, it inevitably turns out they’ve developed a niche product within a large industry, and their market opportunity is only $20 million.

Founders seem to think that big numbers will grab investors’ attention, but wild claims only lead to skepticism about the entire pitch. What matters is not the industry size but the opportunity for your particular product.

Smaller is often better, anyway, since smaller markets are easier to break into without having to invest millions on Super Bowl ads.

But whether the opportunity is big or small, what investors need is a realistic market analysis that explains the opportunity rather than breathless claims of huge markets that say nothing about the company’s prospects.

When I mentor startups, market sizing is usually the first thing we work on since the business plan has to be driven by market need, not product idea. Unfortunately, most TAM/SAM/SOM analyses that I see are a mess.

So here’s what you need to know about market sizing and how to provide the information investors are looking for in your pitch. Instead of trying to get us excited about the size of the market, impress us with your industry knowledge and show you fully understand the specific opportunity you’re attacking.

What are investors looking for?

After a short description of the problem and the solution you’ve developed, the next slide in the pitch should be the market size. It tells us who the customers are, how many there are, and how you plan to compete.

The overall goal of the pitch is to convince investors that buying equity in your business is a good investment that will pay off with a huge return. This will happen because the company will grow at exponential rates to reach $100M+ in revenues within a few years and be acquired, or stay on a trajectory towards $1B+ in revenues and do an IPO.

If the entire market opportunity is $25M, there’s no way to reach $100M so the company unfortunately is not suitable for venture investment. If the opportunity is $250M, then getting to $100M and beyond is entirely possible, but it means dominating the market. If the market opportunity is $50B, then the challenge is not the market size but competing in a crowded space.

So if you’re going after what is obviously a huge market, consumer packaged goods for example, or a new battery technology, you don’t need to say much more than it’s a $50B opportunity and move on to the bigger challenges.

But if you’re building a niche product, the size of the market is often the difference between investing or not, and we need to understand the details.

What is a “market opportunity”?

The first mistake most founders make is misunderstanding what is meant by “market opportunity.” It is NOT the size of the entire industry. Nor does it include pass-through revenue.

The current size of the Li-ion battery market is somewhere around $70B. A nice huge market. If you’re developing an entirely new battery technology that will replace Li-ion batteries in electric vehicles, laptops, phones, etc., then that’s your market size.

However, if you’re developing a new coating for the cathode of a Li-ion battery, then your market size is the total potential sales for cathode coatings in Li-ion batteries. Obviously, this is a much smaller subset of the entire battery industry. How big? I have no idea. That’s why I need you to tell me in the pitch. That’s the “total addressable market” that we use as the starting point.

If you’re developing an e-commerce platform for bowling equipment, and the entire market for bowling equipment is $10 billion, if you take a 10% commission on sales, then your total opportunity isn’t $10 billion but the $1 billion your platform could potentially generate.

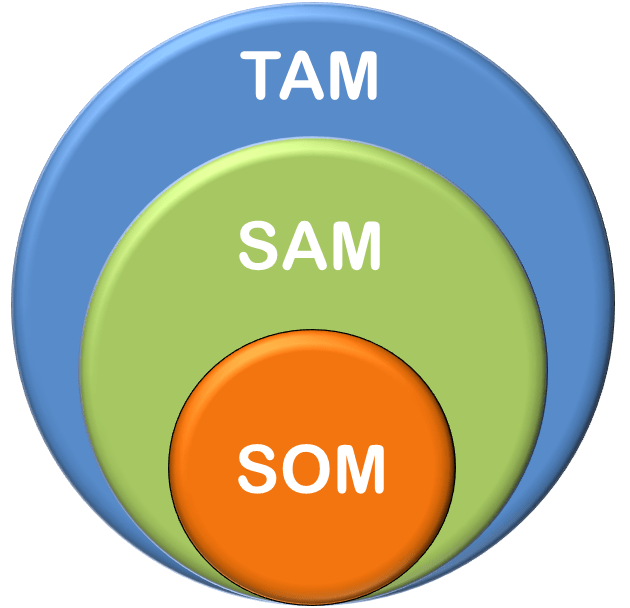

Understanding TAM/SAM/SOM

TAM is the “total addressable market.” That’s not the total industry size but the total market for your product. If everyone who needed your product bought it, how much revenue would that generate annually? If you’re making a cathode coating, it doesn’t matter how big the market for batteries is. I need to know the market size specifically for cathode coatings.

SAM is the “service addressable market.” From the TAM we subtract use cases your product can’t meet. If half the battery manufacturers are in China and they won’t buy from an American company (or you’re precluded from selling into China), then half the addressable market is unavailable. There may be use cases that require longer cycle life, or lower cost, or other factors that aren’t a fit for your technology. When you subtract out the segments of the market that your product can’t reach, you’re left with the serviceable market.

SOM is the “service obtainable market.” The SOM subtracts from the addressable market everyone you could sell to but who won’t buy from you. Usually that means competition or alternative solutions. If you expect 3 competitors to split the revenues evenly, the SOM is one-third of the SAM.

Most importantly, the SOM is how much revenue you expect to generate when you’ve sold to everyone you can. It might take 5 years to saturate the opportunity or it might take 50, but this is the upper limit on revenues for your product. After growing exponentially, revenues for the product will eventually level off and approach the SOM asymptotically.

The SOM needs to be consistent with the 5 year revenue projections later in the deck. If the SOM is only $20M, revenue projections of $50M in year 4 don’t make sense. If the SOM is $70B, why are your revenues leveling off at $100M instead of growing exponentially to $50B?

The point of market sizing is investors need to know how big the company can potentially grow. So the only number that matters is the SOM. However, looking at the TAM/SAM/SOM answers a lot of contextual information in a simple graphic that we can digest in a glance:

- Who are the actual customers?

- What are the various market subsegments and which ones can you compete in?

- Do you expect to dominate a small market or have a small share of a large market?

- What market share do you anticipating reaching?

Do your homework

The TAM/SAM/SOM breakdown is great in theory, but often challenging to put into practice. It’s perfect for biz school projects but often hopeless in the real world where the numbers aren’t available, especially for niches where there is no published data, or products for entirely new markets that don’t already exist.

Finding the size of the battery market is easy. Finding the size of the cathode market is tougher. Finding the size of the cathode coatings market is probably impossible without inside information. (Just to reiterate: the TAM here is the cathode coatings market, not the battery industry.) Breaking down the submarkets is yet another level of complication.

But, as investors, we expect you to do your homework. It’s not enough to say the market for batteries is huge unless you’re developing batteries rather than cathode coatings. If you’re planning to spend millions of dollars and years of time developing a cathode coating, you’d better know exactly who needs it, how much they’ll pay for it, what the sub-markets are, and which sub-markets you can penetrate and which you can’t. We don’t expect you to have a crystal ball to know what will happen in 5 to 10 years, but we do expect you to have a well-researched plan with which to make informed decisions.

But most pitches from early-stage startups quote some report they find online that gives a huge number for industry size, then throws in an estimate for market share and calls the market sizing exercise done. That’s not good enough.

Market sizing is an integral part of customer discovery and takes time and analysis. If you’re in a niche market, it’s arguably more important than product development since it informs what product to build and how to bring it to market. It doesn’t come from a report you buy, but distilled from what you’ve learned talking to customers, distributors, industry experts, and even competitors.

Estimating Market Sizes

There’s 2 ways to do market sizing: top down and bottom up.

Top down: The TAM/SAM/SOM is inherently a top down approach of estimating your expected revenues. Start from data for your specific market, if available, or estimate it from whatever market data is available such as the industry size. If all you have is the size of Li-ion battery market, try to figure out how much the cathode coatings market would potentially constitute — 1%? 5%? 10%? Then estimate the SAM and SOM to get to your expected revenues.

Bottom up: How many customers are there? How much would each pay for your product? That’s your potential annual sales.

Of course, neither top-down or bottom-up method is easy or accurate, but there are a few useful shortcuts:

- industry expertise: talk to competitors (hang out with their salespeople at trade shows and it’s amazing what they’ll tell you), distributors, resellers, and customers who have a wide view of the industry.

- competitor analysis: add up the sales of all the existing competitors and you have the current market size. Or if you know one competitor has half the market, find the revenues for that product and double for the market size. Read and analyze the annual reports from every competitor in the space that makes information available. The detailed notes buried deep in a 10-K filing can be gold.

- proxy products: find other related products sold to the same customers. If battery manufacturers spend $2B on electrolytes, you can use that to estimate the potential size of cathode coatings.

- money or time savings: how much time or money would your customers save by using your solution? You should be able to capture a percentage (more like 10–20% than 50%) of those savings.

Nail the Pitch. And the Diligence

Yes, you might get investors’ attention momentarily by claiming a $47.9 billion dollar market opportunity, but you’ll lose credibility as soon as we realize your product is a small niche within the big industry.

We’re a lot more impressed with a claim of a $2B opportunity with no competitors and a completely unmet need. Then we’ll be really impressed when we get to the detailed discussion and you walk us through each submarket with different requirements and competitors and perhaps an adjusted product and market strategy for each.

In the end, we’re a lot more likely to invest in founders who impress us with their industry knowledge and detailed planning for how to bring their product to market than inflated claims of huge opportunities that are little more than hot air.

In my novel, To Kill a Unicorn, the Silicon Valley startup, SüprDüpr, lands a billion dollar investment from BiteCoin Ventures. But the reclusive Satoshi Nakamoto on their board sends them in a sinister direction.

Get your copy today!

https://amzn.to/3RQnLuc